The must-have questions for a UX research intake form

How to build UX research intake forms that stakeholders actually use

Intake forms help UX teams streamline the process of collecting user research requests, building a backlog of potential projects, and prioritizing them into a roadmap. But they need to strike a delicate balance.

On the one hand, collecting detailed information allows the UX team to wrap their heads around a research request and the context behind it. On the other hand, every additional question included in the form increases the friction for the stakeholder making the request.

An overly long request form is unlikely to be used by our stakeholders — they may give up halfway through, avoid using the form altogether, and form the misperception that UX research is an overly burdensome process. When creating an intake form, UX practitioners should prioritize the questions included to get just enough information to understand the ask, its scope, and timelines.

Building a UX research intake form that stakeholders will use

The first step in building a form that stakeholders will use is deciding where to create and host it. There are many tools for creating a form, but generally, you want it to be easy for stakeholders to find and use whenever needed. Ideally, you would co-locate your form with something your stakeholders already use or a system they’re familiar with. For example, this could be:

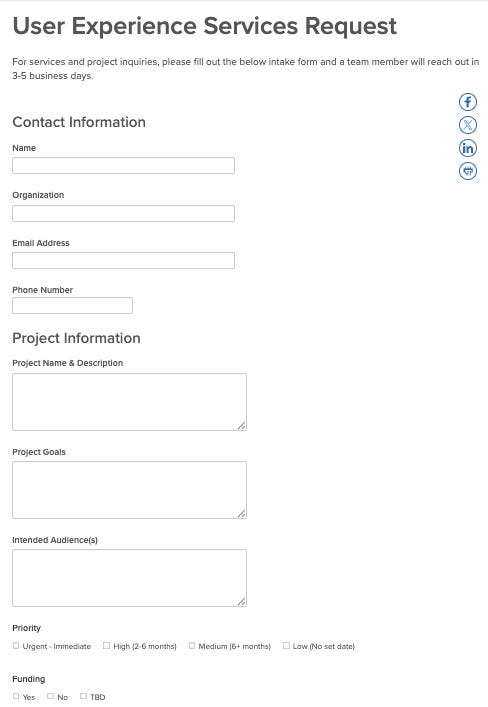

A custom webpage, like this example from Columbia University, could be particularly useful if your stakeholders are frequently on a company intranet.

A work management system like Trello, Google Forms and Sheets, Monday.com, or Notion. These platforms can fit into existing project management workflows and include helpful integrations and automations that make organizing requests simple. Here, you can see Odette Jansen's Notion request form.

A simple template document. If stakeholders in your organization frequently use tools like Google Docs for project planning, a request template like Nikki Anderson's might be useful.

Once you decide where to host the form, the next primary consideration is determining what information to collect, ensuring you gather enough background without creating unnecessary friction for stakeholders.

What to include in your UX research intake form

User research intake forms can capture a variety of project information. It’s helpful to organize this information into categories based on priority and relevance to decide what to include in your request form. Some questions are essential and will be used in every form, while others are useful but optional. Certain details may only be valuable in specific contexts, and some are better left out entirely. Let’s break these different groups down:

The essentials are the foundational pieces of information every intake form needs to provide clarity and context while keeping the process efficient for stakeholders. The six essentials are:

Set context for the requester — A good intake form should clarify what happens after submission, including when and how you will respond, expected timelines, and how you prioritize requests. Setting this context helps stakeholders understand the form’s purpose and what to expect next. Once they understand the context, you can begin to ask for information.

A project name — Giving the request a project name makes it easier to reference and track the request.

Research goals or objectives — Ask the requester what they want to learn, the potential impact of that information, and how they plan to use the findings. This ensures you understand their underlying objectives and what they hope to achieve.

Background — Ask for any additional information that explains why the research is being requested that can help you interpret their goals and objectives more effectively.

Important dates — Stakeholders usually request research to support specific initiatives, such as a product release or a key decision. Knowing the ideal timing, or even the last date where findings would be useful, allows you to plan accordingly.

Name & Contact — This is straightforward but critical—you need to know who submitted the request and how to follow up with them.

If you wanted, you could stop with these six items. However, you could also carefully consider adding 1-2 of these Useful additions — information that is typically useful but not essential and adds to the length of your form. Only include items from this list if you feel they will add substantial value to your scoping and prioritization of requests. Every additional question should be weighed against its potential to deter stakeholders from completing the form, so even if you include them, it is best to mark them as optional.

User details — Information about the users involved, such as personas, user groups, demographics, or other key characteristics. This is particularly helpful if you have multiple different user groups.

Needs or Jobs to be Done — The specific user need or task the request relates to.

File uploads — A space for stakeholders to share relevant documents related to their requests.

Product line or area — For organizations with multiple products or large websites.

Success criteria — Ask what success looks like. For example, are they aiming to increase feature adoption or a specific KPI?

Finally, you might consider if any Context-dependent extras are needed. These questions might be helpful in specific situations but often depend on familiarity with user research and UX outputs and should only be included if the rest of your form is sufficiently brief.

Research method & Details — If your stakeholders are familiar with various types of user research and have specific methods in mind, you could ask about their preferences. However, asking stakeholders to select methods may lead to uninformed choices.

Assumptions — When planning research, there are often underlying assumptions. If your stakeholder has research experience, they may be able to share these assumptions, which could help shape the project.

Desired deliverables — If your stakeholders are familiar with user research outputs they might request something specific. So, you could consider providing options to help them indicate what they are looking for (e.g., raw data, PowerPoint report, topline summary, charts, or a specific UX artifact like a journey map)

Level of support — Depending on your organization, you might offer different levels of research involvement. This is particularly relevant if research democratization is a priority on your team. Consider allowing stakeholders to indicate whether they need help with planning, recruitment, conducting the research, analysis, or any combination of these.

Budget — This is very context-dependent, but for some teams, it will make sense to ask if a project has received funding during the request phase, so they don’t prioritize it before budget is in place.

Drawing from the three categories above should be sufficient for any research intake form. Anything beyond this we can consider as part of “The don’t list.” In theory, the set of things we shouldn’t include in request forms is infinite (e.g., the stakeholder’s coffee order). In practice, there are two types of questions commonly found on intake forms that should be excluded:

Decisions that should be left to the research team, like sample sizes, proposed participant incentive amounts, and research tool preferences.

Information that can be determined at project kickoff, like preferences for meeting times and preferred channels for project communications.

To keep your request form concise and effective, include the essentials and select only a few useful additions or context-dependent extras, as needed—while leaving out anything from the “don’t list.”

Once you have a draft of the form, test it with your UX team first. Aim for a clear goal, like ensuring the form can be completed in 10 minutes or less. After finalizing your draft, release it for a pilot by promoting it to stakeholders through multiple channels (e.g., email announcements, team meetings, workshops, or chat threads). Use feedback and observations from your pilot period to further refine the form, ensuring it provides the information your team needs while respecting your stakeholders’ time and effort.

The bottom line

Research intake forms can help a UX team effectively triage incoming requests, but they need to strike the right balance to be effective. Too short, and they result in time-wasting back-and-forth communications to fill in gaps. On the other hand, overly long intake forms create friction for stakeholders and may lead to the misperception that the process of user research is too time-consuming.

When building your research request form, prioritize the information you collect, including the must-haves from the list above, adding other questions only as they are necessary. Focus on collecting the most essential information needed to triage user research requests.

Helpful advice! Keeping forms simple makes them more useful.

In my experience, research intake is most effective as a 1-on-1 meeting to clarify details together -- it has to happen anyway, so why go through the extra, painful steps of them trying to write out (and me trying to interpret) "fill-in-the-blank" answers? A template is merely a reminder of all things to consider. I attach my template to the intake meeting request as a guide to the types of Qs I will be asking, as we figure out next steps together.