When the truth resists simplicity in UX

How embracing complexity can be a good thing for your UX skillset

Boiling down concepts into pithy one-liners can make them easier to grasp and remember. However, the truth often resists simplicity. This principle is particularly true in fields like UX research, where oversimplified explanations can hinder a comprehensive understanding of principles and impede mastery of the craft.

In this article, we’ll explore the aphorism that says “truth resists simplicity,” how it applies to UX research, and its implications for learning and personal development.

“The truth resists simplicity”

John Green is an author best known for his young adult novels, but he has also had a successful YouTube channel for 17 years. Green’s video essays often cover hairy and nuanced topics like the intersection of geopolitics and healthcare. In discussing these topics, Green often says, “The truth resists simplicity” — this has become an unintentional and ironically simple catchphrase that reminds us that reality is rarely black and white.

User experience and geopolitical healthcare don’t share much in common, but Green’s axiom is applicable and useful for UX practitioners. When you’re initially learning a new concept or new field of study, boiling larger ideas into simpler truisms is helpful, but as you deepen your understanding, you will find a need for complexity and context.

Where Green says, “truth resists simplicity,” UXRs say “It depends.” By seeking a layer of nuance, UX practitioners develop a deeper understanding of their craft. Let’s explore a few examples where digging deeper reveals nuances in UX research.

Examples from UX

The five-participant rule

If you’ve been in UX for any time, you’re probably familiar with the five-participant rule for qualitative studies. This convention holds weight; five participants can uncover a significant proportion of usability issues with a design, but it is essential to understand where this number comes from.

The five-participant rule comes from a mathematical model of discovering usability issues that showed n= 5 can uncover 85% of usability issues in an interface. However, an important assumption behind this figure is that it estimates the average usability issue will impact 31% of users. If usability issues with your design are less common, impacting only 10% of users, you would need to test with n= 18 to uncover 85% of usability issues.

Beyond understanding the assumptions behind the equation, it is even more important to understand the context and motivation behind the calculations. The authors exploring discount usability methods were doing cost-benefit analyses, exploring the point where adding more participants yields diminishing returns as compared to redesigning and testing again.

In short, the five-participant rule is based on a cost-benefit analysis and a mathematical model that will tell you how many users are optimal in an iterative testing cadence, with an assumed usability issue probability. If you have an interface where usability issues occur less frequently or a situation where you cannot perform multiple iterations of design and testing, you’ll need to test with more users.

Group interviews

Focus groups are a qualitative method where a moderator conducts a group interview session with 5-12 people to discuss their attitudes toward a product, brand, or service. While they’re a popular method in market research, they’re generally frowned upon in UX. Focus groups provide poor and inaccurate behavioral insights, aren’t well-suited for studying usability or how people actually use a product, are susceptible to groupthink and other negative group dynamics, and sometimes aren’t even good for studying how each individual in the group feels. For these reasons, many UX researchers will say you should never do focus groups.

Every method has its biases and issues; that doesn’t mean we should abandon it entirely. A more nuanced viewpoint shows us that focus groups have a use case, albeit a niche one: they can be a good idea if the real-world use case of your experience is a group setting. For example, I once ran a focus group that tested concepts for an educational game designed for school-age children. The game was designed to be played in groups, so we tested it in a group setting. By testing with a group, we could see what concepts got the kids excited vs. which ones fell flat in a way that we simply couldn’t see in individual tests.

Context and objective play a critical role in the suitability of any research method. Focus groups have more than their fair share of limitations, but they can offer good insights if they’re conducted in the right scenario with an understanding of their strengths and weaknesses.

Qual answers why, Quant answers what

When explaining the merits of different types of research, someone might say, “Qual answers why” and “Quant answers what.” While easy to grasp, it’s an overly broad explanation that wares out its initial utility quickly. If we don’t give them anything else to go on, stakeholders might misunderstand the capabilities and limitations of research methods (i.e., underestimating the exploratory power of quantitative research or the explanatory power of qualitative research). This misunderstanding, in turn, could lead to off-base suggestions for what type of research should be included in a project, or unrealistic expectations for the type and certainty of the answers a research project will produce.

You can still give an elevator pitch for quant and qual research by quickly summarizing what they are, example methods, and what they’re good for. For example:

Qualitative research collects non-numerical data about our users, in the form of observations or direct feedback. The most common qualitative methods include user interviews, qualitative usability tests, and ethnography. These methods can be useful to address objectives like uncovering user motivations and needs, developing an understanding of the user’s context of use, or identifying usability issues.

Quantitative research gathers numerical data about users’ attitudes and behaviors. Some of the most common quant methods include quantitative usability tests, surveys, and A/B testing. These methods can be useful to address objectives like identifying trends in user behaviors, measuring the effectiveness of design changes, or determining the scale of an issue.

These two bullets take less than a minute to say and offer a more compelling overview of the general utility of qualitative and quantitative methods without getting too far into the weeds.

Fitts’s Law & Boundary conditions

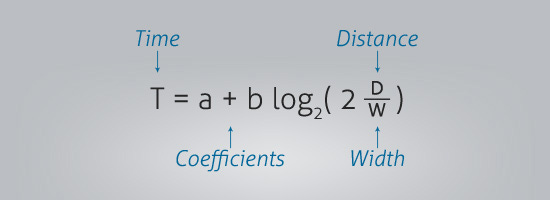

Fitts’s Law is a model that predicts the time it takes to tap a target object based on its size and how far away it is. Essentially, it takes you longer and is more difficult to tap objects that are farther away and/or smaller. In UX, Fitts’s Law is often applied to inform the design of buttons, namely making them larger and optimized for distance.

In his original experiments, Paul Fitts set up a series of different testing apparatuses (example below) that required participants to tap back and forth on targets of varying sizes and distances from each other. You’ll notice all these experiments were physical — they’re from the 1950’s after all — so, how well does Fitts’s Law transfer to digital interfaces?

As it turns out, Fitts’s Law does a pretty good job of predicting pointing, and clicking with a mouse. However, user interactions are rarely limited to an isolated point-and-click sequence. Further studies demonstrate context effects that exhibit how different actions like dragging, the direction of movement relative to the shape of a button, or error penalties (i.e., situations where missing the target produces negative effects for the user) can greatly impact how well Fitts’s Law applies to an interaction pattern.

The bottom line

When first learning user experience, simplifying complex ideas can be helpful, but a deeper understanding requires confronting the inherent complexity of the subject matter. Acknowledging that the truth resists simplicity, and actively seeking out nuance is crucial for developing a deeper understanding that allows a UX practitioner to make well-informed decisions and avoid oversimplification.

UX researchers should embrace complexity and seek to understand the assumptions, limitations, and context behind established practices and guidelines.