When to use conjoint analysis in user research

Prioritize features & Shape product strategy

Conjoint analysis, while relatively popular in market research, is not particularly common in user research. Our analysis found that only 1% of user research job descriptions included conjoint as a required or preferred skill.

Yet, there is clear interest in the method. In a recent LinkedIn poll of UX professionals—admittedly, non-scientific—over 50% said they had never used conjoint analysis but would like to learn more about it. This makes sense, as market researchers and UXRs often seek to answer similar questions like: “Which product improvements would have the greatest impact on satisfaction?“ or “Which features matter most to our users?“

Despite this interest, many researchers don’t know when to use conjoint analysis. This article will help by outlining three specific scenarios where the method can be highly effective, including prioritizing a set of features, identifying the best combination of features for a single product, and building a suite of products that cover diverse user needs.

Conjoint analyses: A quick Primer

Conjoint analyses help answer a foundational yet challenging question in product design: What is the combination of product features that maximizes user satisfaction? Conjoint surveys typically present users with a set of products (usually 2-4) and ask them to indicate their preferred option. Each product consists of attributes and levels:

Attributes are features or characteristics of a product or interface

Levels are a specific variant of an attribute

For example, imagine you were purchasing a car – color might be an attribute, while blue would be a level. Below you can see an example of a typical conjoint study from OpinionX.

It’s worth noting that there are many variants of conjoint studies, often broadly referred to as “discrete choice analyses.” But they all generally follow this pattern of presenting the respondent with a set of products or features and asking them to make a discrete choice to indicate their preference.

By presenting several product combinations to an appropriate sample size (typically in the range of n= 150-300 or more), we can analyze how users make tradeoff decisions between features. Through these quantitative analyses, we can rank the importance of attributes, identify user preferences for levels within those attributes, determine the most preferred feature combination, or even estimate preference share to gauge how a product might perform in the market. These insights allow product teams to optimize packages, plans, and pricing. With this foundational understanding, let’s explore three scenarios where conjoint can be useful.

Conjoint analyses: Use cases in user research

1. Identify the best combination of features for a single product

A common use of conjoint analysis is to determine which specific combination of attributes and levels results in the single most preferred product. You might be in this scenario if your stakeholders have questions like, "What combination of features will maximize satisfaction, purchase intent, or subscriptions?"

To answer this, you would define the attributes and levels for your test, listing the key features and their variations. Then, create a conjoint survey where respondents are presented with combinations of the attributes and levels and asked to select their preference.

After collecting responses, you can analyze the data to examine the relative importance of each attribute and the preferences for levels within each attribute. However, you’ll also examine how specific concepts (i.e., a specific combination of attributes/levels) rank relative to each other. For example, a concept report—like the one from OpinionX below—ranks every possible product and assigns each a score.

To illustrate this use case, imagine a tech company is developing a new laptop and wants to maximize consumer appeal. They are considering multiple attributes, including:

Screen size: 13", 15", 17"

Processor speed: i5, i7, i9

Battery life: 8, 12, or 24 hours

Touchscreen capabilities: Touchscreen or no touchscreen

Price points: $1,000, $1,500, or $2,000

A conjoint analysis would help determine which combination of these features creates the most desirable laptop for their users. The result might show that a 15-inch laptop with an i7 processor, 12-hour battery life, no touchscreen, and a $1,500 price point is the most preferred combination.

You can use this analysis to determine which product concept is most compelling and maximizes user preferences. However, keep in mind that your “winning” concept may not be a runaway winner; the difference between the top-ranking options might be within a margin of error, meaning either could be a strong choice.

2. Prioritize a set of features

You might find yourself in a situation where you want to assess the relative importance of different features rather than identifying the best combination of attributes and levels for a single product. In those cases, you could use a MaxDiff analysis, a variation of conjoint that helps you rank features (or attributes) by importance, providing a clear sense of user preferences. This type of analysis is useful when you’re answering questions like:

Which features matter most to our users?

Which features should we invest in first?

Are there any features that we could de-prioritize without negatively impacting satisfaction?

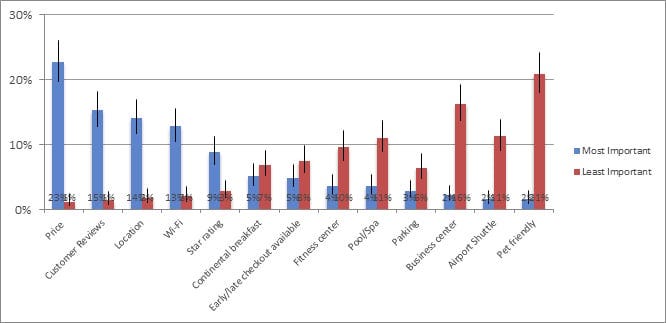

A MaxDiff survey presents respondents with a subset of features and asks them to choose which is the most important and which is the least important. Analyzing the results of these responses quantifies the importance of each feature in your test. For example, below, you can see the results from a MeasuringU MaxDiff analysis on the most and least important features for hotels.

Continuing the example from earlier, imagine that the tech company is in the early phases of developing concepts for their new laptop and wants to understand where they should focus their efforts. A MaxDiff study can help them determine which features matter most for their next-generation laptop. They might test:

Battery life

Screen size

Processor speed

Storage capacity

Touchscreen functionality

Weight

The results might show that processor speed, screen size, and battery life are significantly more important to customers than other features, while touchscreen functionality ranks lowest. Based on this insight, the company could prioritize improvements in performance and portability rather than investing in touchscreen technology.

MaxDiff is a relatively simple but powerful discrete choice analysis. It helps you understand the relative importance of features but does not determine their optimal combination. Use MaxDiff when you need a clear, ranked list of feature priorities to align stakeholders quickly. However, if you need to determine the best combination of features for a single product, the ideal price point, or the optimal suite of products for a portfolio, MaxDiff isn’t the right fit.

3. Optimize a set of products to cover more user needs

What if, rather than developing a single product, you wanted to make a product lineup? This is a relatively common scenario — companies often create a suite of offerings that meet the varied needs of different user groups rather than designing just one product. When creating a product portfolio, a team might have questions like:

How can we develop a set of 2-3 distinct offerings that cover a majority of users’ needs while minimizing overlap?

How can we design tiered product plans?

The methodological setup for this question is the same as the first use case we reviewed (i.e., define attributes and levels and run a conjoint survey). However, additional analysis methods are required to answer these research questions. The challenge is that you can’t simply select the top i ranked concepts to develop a product portfolio of size n= i. The top-ranking concepts may all appeal to the same type of user, leading to significant preference overlap.

Specialized analysis is needed to select a product portfolio that minimizes this overlap. There are a couple of approaches that accomplish this:

Total unduplicated reach and frequency (TURF) - This calculation identifies the concepts that maximize the coverage of user preferences for a given product portfolio size (n= i).

Genetic algorithmic optimization - As described by Chapman and Alford in their 2010 conference presentation, another approach is to use genetic algorithms to generate random sets of product portfolios and iterate until the user preference share percentage doesn’t improve.

Both methods help determine the optimal number of products for a portfolio and identify the specific products to include, ensuring broader market coverage and better alignment with diverse user needs.

For example, instead of designing a single laptop, imagine we wanted to create a product line with varying features and price points. We could use TURF or genetic algorithms to determine the optimal catalog of three laptop models. The results might suggest that an ideal portfolio would include:

A premium laptop with long battery life, a lightweight design, and a high-end processor

A gaming laptop with a high-resolution display, a larger screen, and a powerful graphics processor

A budget-friendly laptop with decent battery life, affordability, and portability

These techniques are some of the most advanced applications of conjoint analysis. If you have access to tools with these capabilities built-in, it can be relatively straightforward. If you’re comfortable with elegant quantitative analyses, you might be able to do it manually yourself. However, in many cases, you might need specialized software or the help of a data scientist to run these analyses effectively.

The bottom line

Conjoint analyses aren’t commonly used in UX research, but they have remarkable potential for informing product decisions. This article explored three use cases for where these methods add value:

Optimizing the feature set for a single product

Prioritizing a set of features by relative importance

Designing a suite of products that meet diverse user needs without overlap

Beyond their standalone value, these methods serve as a strong quantitative complement to exploratory methods like interviews or ethnography by validating qualitative findings and measuring user preferences. When used together, these techniques can inform product roadmaps with greater confidence.

With this foundation, UX researchers can recognize when to use these techniques and use the provided reference materials and tools to implement them in their work.

Great guide, Thomas! 👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻

Really interesting breakdown. Conjoint analysis seems like a game changer for cutting through the noise and figuring out what users actually care about not just what they say they want. Has anyone tried running a smaller scale conjoint study for early stage products? Would love to hear how it worked out or if there are better lightweight methods for feature prioritization.