When it makes sense to test interface components in isolation

Why early testing of isolated UI elements improves usability

User research rightly emphasizes testing products in realistic scenarios and contexts. However, in some cases, selectively testing isolated interface elements can be a quick way to uncover issues with early designs.

This article outlines when isolated testing is beneficial and how to structure those tests effectively, including three examples: icons, copy, and menus. When used responsibly, isolated testing can be a valuable part of a broader research approach, providing quick feedback and enabling iteration on early design elements without abandoning the importance of context.

Why context matters in user research

Testing interfaces in realistic contexts produces more valid research findings, resulting in better design decisions and better products.

Well-planned product research accounts for context, ideally across three dimensions: users, tasks, and scenarios.

Representative Users

We want to make sure we’re testing with representative users, meaning people who would actually be the ones using the product. They bring a specific mindset, expectations, behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, and domain knowledge shaped by their experience. Testing with stand-ins, whether that’s a teammate or a gen-pop participant who doesn’t match the product’s actual target user, can lead to misleading results or overlook critical ways real users would interpret or interact with the product.Representative Tasks

Users don’t just click around randomly; they interact with products to achieve specific goals, which we refer to as tasks. Well-designed research is often task-based to ensure the product supports goal-driven interaction and decision-making.Representative Scenarios

Scenarios refer to the situation in which the user engages with the product: where they are, what’s going on around them, how they’re accessing it, and what their mental state might be. Environmental and situational factors, like distractions, urgency, or lighting, can influence both comprehension and usability. For example, a feature that’s perfectly usable in a quiet office may become confusing or go unnoticed by someone on a noisy subway.

This trifecta -representative users, tasks, and scenarios- captures the real-world complexity that digital products must be designed to accommodate. Effective research aims to account for all three.

However, there are times when it makes sense to run quick, early tests of specific interface elements outside of a full task flow or realistic scenario.

The case for isolated testing

Isolated testing of interface components can be valuable early in the design process as a precursor to in-context user research.

Just like a builder might inspect their materials before constructing a wall, designers can validate interface elements before assembling a complete experience. In the early design phases, while you're still working with sketches, wireframes, or low-fidelity components, it can be useful to get quick feedback on basic comprehension, recognition, or clarity. Doing this early helps surface issues before investing significant time or effort into higher-fidelity design.

Not everything needs to be tested out of context, but in some situations, it’s useful to test individual components first, then follow up with task-based, in-context testing once the full flow is ready.

A two-step approach is often best.

Isolated testing. This is useful for early-stage feedback before full designs are ready. You might validate components for clarity, recognition, or effectiveness using methods like first-click tests, comprehension studies, targeted surveys, or card sorting. The goal is fast iteration and early issue detection.

In-context research. Once components are placed in realistic flows, you can evaluate whether they come together to support the user’s goals through task-based research with representative users and scenarios. This step uncovers system-level usability issues, unclear visual hierarchy, or interactions between elements that weren’t apparent when tested in isolation.

Whenever isolated testing is used, it should always be followed by contextual testing. Interactions between elements, environmental factors, and task context all influence how users understand and navigate the experience. Isolated testing is not a substitute for in-context research; it’s a supplement. Used selectively, this two-step approach can lead to a more efficient design process and ultimately more user-friendly products.

Let’s look at three examples of when this approach makes sense: icons, copy, and menus.

Example 1: Icons

It can be useful to evaluate early illustrations of icons to ensure they are recognizable and interpreted correctly by users before they go into a fully designed task flow. At this stage, we can test for recognition, distinctiveness, and meaning, even while the broader experience is still being designed.

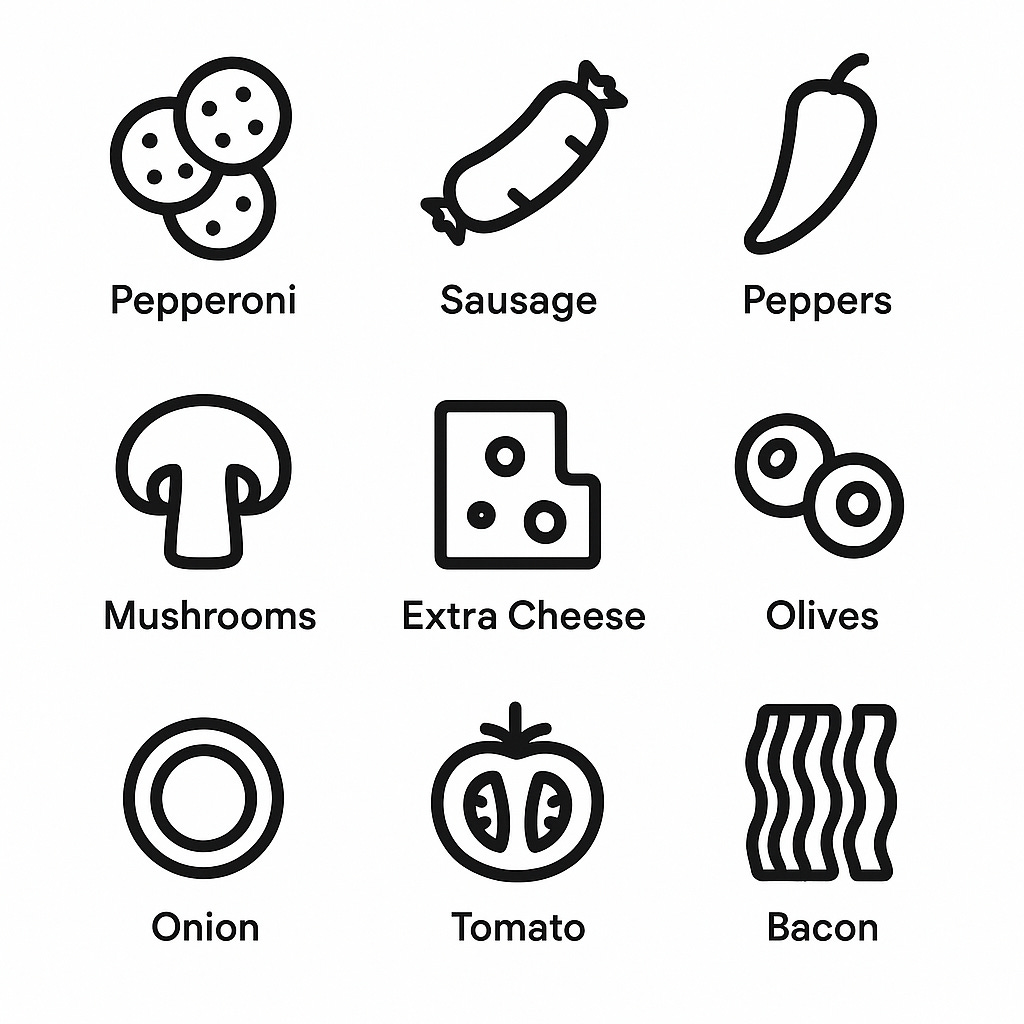

For example, imagine we are working on the order customization flow of a pizza delivery app. A designer has created a set of draft buttons, with each one using an icon to depict a different topping.

We want to make sure users can easily recognize these icons, so we set up a simple survey:

Half of the participants are shown the icons individually and asked, through an open-ended question, what each one represents.

The other half is shown the full set of unlabeled icons and asked which one they would tap to select a particular topping in a first-click test.

We then analyze the results by coding the correctness of the open-ended responses and reviewing the accuracy of the first-click selections. We might learn that our onion and pepperoni icons are not particularly recognizable and need refinement before we move forward with integrating them into the ordering flow.

Example 2: Menus

Testing menus and organization outside the context of an interface can help assess how well the information architecture’s structure and grouping align with user mental models and support finding information quickly. These are commonly assessed in tree tests and card sorts, where IA elements are presented in plain text rather than fully-fledged interfaces.

Imagine you were redesigning a product’s account settings menu (e.g., Profile, Notifications, Settings, Security, etc.). Before implementing the revised menu, you might choose to set up a tree test to evaluate how well users can locate functionality within the hierarchy using intent-based tasks (e.g., where would you expect to click to change your password). We can analyze overall success rates and directness to inspect the findability and clarity of the new structure.

Example 3: Copy

Finally, testing copy in isolation can help validate that users clearly understand the message before it's placed within the larger context of an interface. By doing so, we can detect issues like confusing phrasing, missing context, or misaligned tone before those issues are embedded in a full design.

There are many different ways to test copy, depending on what you want to evaluate. You might focus on comprehension to check whether users grasp the key points. Or recall, which assesses whether they can remember the message after a short delay. You can also evaluate tone and sentiment to ensure the message comes across as intended, such as being helpful, reassuring, or aligned with your brand voice.

For example, imagine we’re working on a system outage banner. You’ve drafted a message intended to keep users informed about which features are affected, when the service will be restored, and how to obtain help. While the team begins designing the notification UI, you decide to test the copy for comprehension.

We can set up a five-second test where we briefly show the message to users, then ask them to elaborate, in their own words, what the message is communicating. We can then code their responses (e.g., correct, partially correct, or incorrect) to see which parts of the message may need editing for clarity before later implementing it into a prototype for further in-context testing.

The bottom line

Testing UI elements in isolation can be an effective precursor to contextual, task-based research. Early in the design process, isolated tests can be used to uncover issues like icons with recognition problems, unclear copy, or poorly organized menus before integrating these elements into full task flows, and later in-context testing to ensure holistic usability. When used selectively, this two-step process can be an efficient use of time and resources and ultimately produce better product experiences.