Writing effective recommendations from user research findings

Learn when to recommend, how to choose the right level of detail, and the FIRE structure for maximum impact

Compared with designers (who shape the interface and interactions) and engineers (who build the technical infrastructure that powers it all), researchers focus on the users themselves. We want to understand what their needs and expectations are, and where interactions cause confusion or errors. But to truly influence product and digital strategy, we must be comfortable translating that into at least a high-level outline of potential solutions.

This article will explore how to decide when (and at what level) to give recommendations, how to effectively situate and prioritize them within a report deliverable, and how to summarize them for actionability.

Should researchers write recommendations?

This is a common and understandable question. Although user researchers often lack a design or engineering background and the precise context to dictate exact implementation or final form, they are experts in the users, their needs, and their pain points. This gives them a unique and valuable perspective on how solutions might manifest within the product or experience itself.

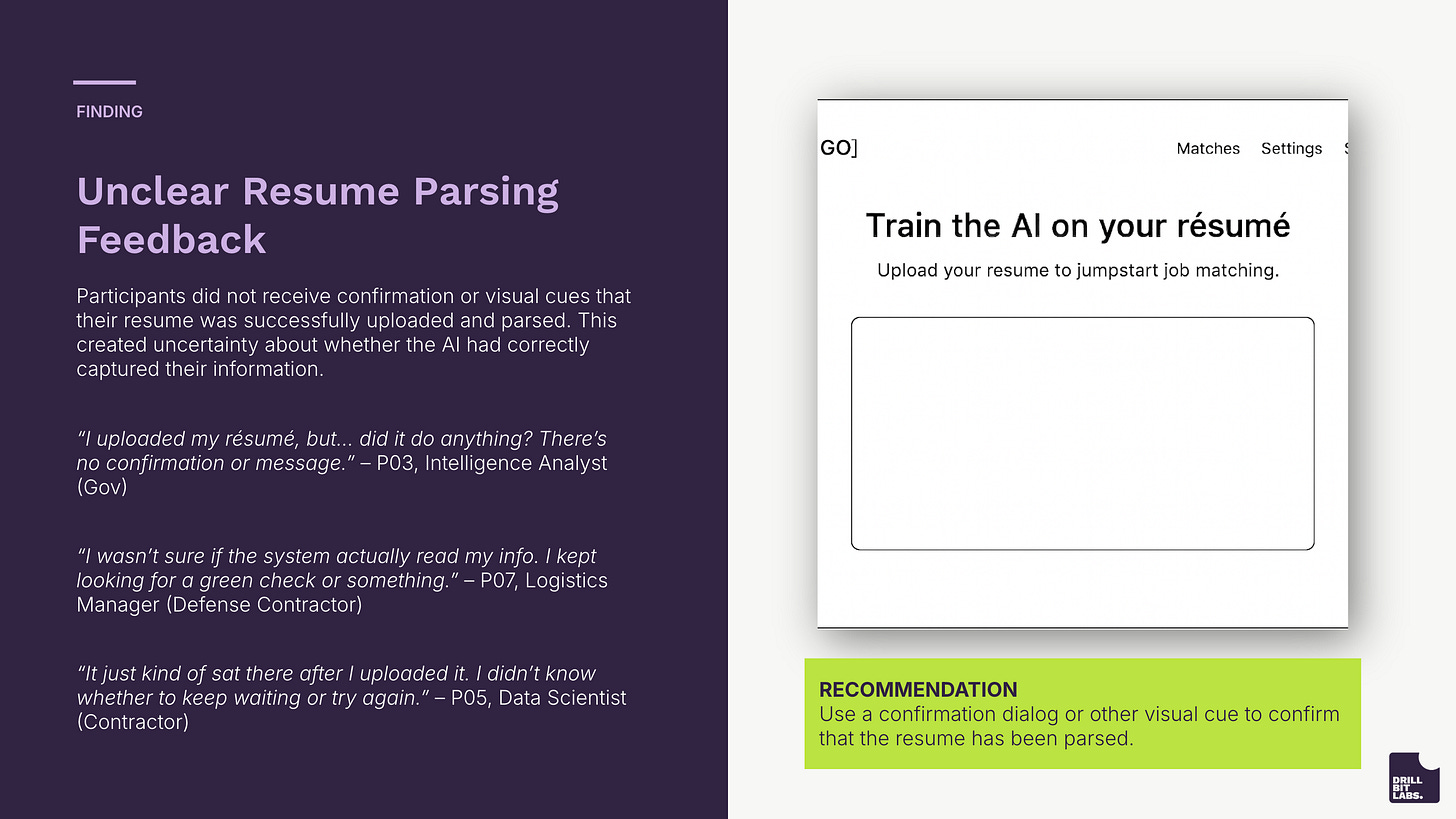

A recommendation is simply a practical instruction guiding a product development team on how to address a research finding, whether by making an improvement or fixing an issue. They generally live within a report deliverable, regardless of its specific format. For example, they might appear as a designated text box at the bottom of a finding slide in a presentation deck, as illustrated below.

The very name “recommendation” suggests a certain degree of tentativeness. It isn’t a command, nor is it a requirement.

You’re simply giving stakeholders something to consider. The recipient is then free to implement it, adapt it, or even disregard it entirely, based on their best judgment. Consequently, in most situations, there's little downside to providing them. At the very least, recommendations offer the significant upside of demonstrating that you've thoughtfully considered the implications of your findings.

Of course, not all recommendations are equal. What works for one researcher, one team, or one company might look totally different elsewhere. Let’s look at how some of those variables influence the recommendation.

Three approaches to recommendation depth

The appropriate level of detail for your recommendations depends on the established working relationships and communication norms with your report’s intended audience.

Recommendations can manifest in one of three primary forms: no recommendations at all, low-resolution recommendations, or high-resolution recommendations. In practice, these latter two categories exist along a continuous spectrum rather than as rigid choices.

No Recommendation: On some teams, there may be a desire to independently digest findings and determine what actions should follow. This approach might stem from an operating model that mandates discrete hand-offs, assigning recommendation responsibility to another specific role. Corporate culture can also play a part. For instance, an engineering team might historically interpret recommendations more literally than intended.

Regardless of the underlying reason, the optimal strategy here is to refrain from providing explicit recommendations. If you believe there are good reasons to challenge this policy, the most effective course of action is to start a discussion in an appropriate forum, rather than trying to sneak recommendations into your next findings report. Nevertheless, even here, clearly articulating your findings will help stakeholders formulate their own actionable next steps.

Low Resolution Recommendations: Researchers sometimes find themselves new to a team or engaging with unfamiliar problem spaces. For example, as an internal (or external) consultant brought in for a specific research engagement, you might lack prior product experience, and it may be unlikely that you’ll work on it again. As such, you’re unfamiliar with technical constraints and design decisions that team members take for granted.

While there are times and places for questioning those decisions or constraints, you lack the context to make those judgments effectively. Given this lack of context, the most appropriate approach is to offer directional recommendations. These describe how the user experience should feel or function, rather than providing detailed, prescriptive instructions. For instance, instead of dictating “add a search bar to the navigation,” a low-resolution recommendation might propose, “Users require a more efficient method to locate specific items on the page,” implying a solution without explicitly prescribing it.

High Resolution Recommendations: For researchers who are deeply embedded within a product space — who thoroughly understand the constraints and design conventions, have longstanding relationships with key stakeholders, and perhaps even possess a design background themselves — you are in a much better position to gauge the feasibility of proposed solutions.

Such researchers are able to offer highly detailed instructions regarding the interface itself, outlining its appearance, even down to precise pixel-level specifications. Recommendations of this nature frequently incorporate visual aids such as figures, mockups, or even interactive prototypes, presenting a high-fidelity example of the intended improvement.

When time permits and your audience is inclined to active participation, you may choose to frame low-resolution recommendations as How Might We statements. This approach shifts the onus onto stakeholders, challenging them to collaboratively brainstorm and develop solutions that deliver the outlined experience, effectively guiding them toward an outcome closer to a high-resolution recommendation.

Once you’ve set the dial to the right level of detail, the next task is figuring out the best way to package and present the recommendation.

Structure recommendations for impact

Good recommendations don’t exist in a vacuum. Rather, they are ideally presented within a structured communication sequence (FIRE, for short) designed to foster understanding, build credibility, and ultimately drive action.

Describe the Finding simply and provide any necessary context, such as where it occurs or under what circumstances. Since stakeholders aren’t often direct collaborators in the research, you need to make what happened clear to them. Visual aids like videos and annotated screenshots (using markups such as boxes, circles, and arrows) can be helpful to illustrate.

Detail the core problem and, more importantly, its Implication for the user. What negative effect is it having on the experience? If you are aware of business goals or KPIs that the product team is responsible for, here’s a great place to draw a connection between the issue the user is facing and those metrics. For example, a user’s inability to complete a purchase directly impacts revenue, while expressions of frustration could adversely affect customer loyalty or satisfaction. Include supporting evidence here as well, such as videos or descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies).

Having articulated the finding clearly and concisely and given a rationale for its importance to the product, you then state the Recommendation, ensuring it aligns with the appropriate level of resolution discussed previously. Provide stakeholders with a suggested action designed to address the issues you’ve uncovered.

Follow that up by painting a picture of the ultimate Expectation — that is, the anticipated outcome or benefit that implementing the recommendation would generate. For instance, if a simple tweak would likely help users complete an upgrade that was previously extremely difficult, state that explicitly.

Within the context of the finding, its implication for the product or business, and expected outcomes for solving it, a recommendation is more likely to be understood and much harder to ignore. You can further “light a fire” for action by prioritizing which recommendations should be addressed first.

Help stakeholders choose what to fix first

Since resources are finite and not all problems can be addressed immediately (or even at all, within any given timeframe), we should do our stakeholders a favor and give them guidance on what to tackle and in what order. They may ultimately disagree with what seems most pertinent to address, but you’re still doing them a kindness by “solving the blank-page problem” and creating an initial draft of a plan that they can react to or adjust.

Traditionally, there are several ways to prioritize usability issues. One is simply the frequency of problem occurrence. If an issue affects a majority of participants in a small qualitative sample, it’s likely to affect a substantial number of real-world users.

While sensible, this frequency-based approach provides only a partial picture. An issue might affect nearly everyone but be so minor that it barely registers, causing at most a negligible delay or slight irritation. Conversely, certain issues may occur very seldom during a usability test yet qualify as “show-stoppers” — meaning a user encountering such a problem would be entirely unable to resolve or recover from it, leading to a critical failure with severe negative consequences.

This is why we consider both frequency and severity. Even rare, highly consequential issues often warrant higher priority.

It’s wise to combine both frequency and severity when making judgments about issue priority. Nevertheless, the final determination is less about punching these values into a calculator, and more about blending them with your intuition. These judgments are part of your unique contribution to the team.

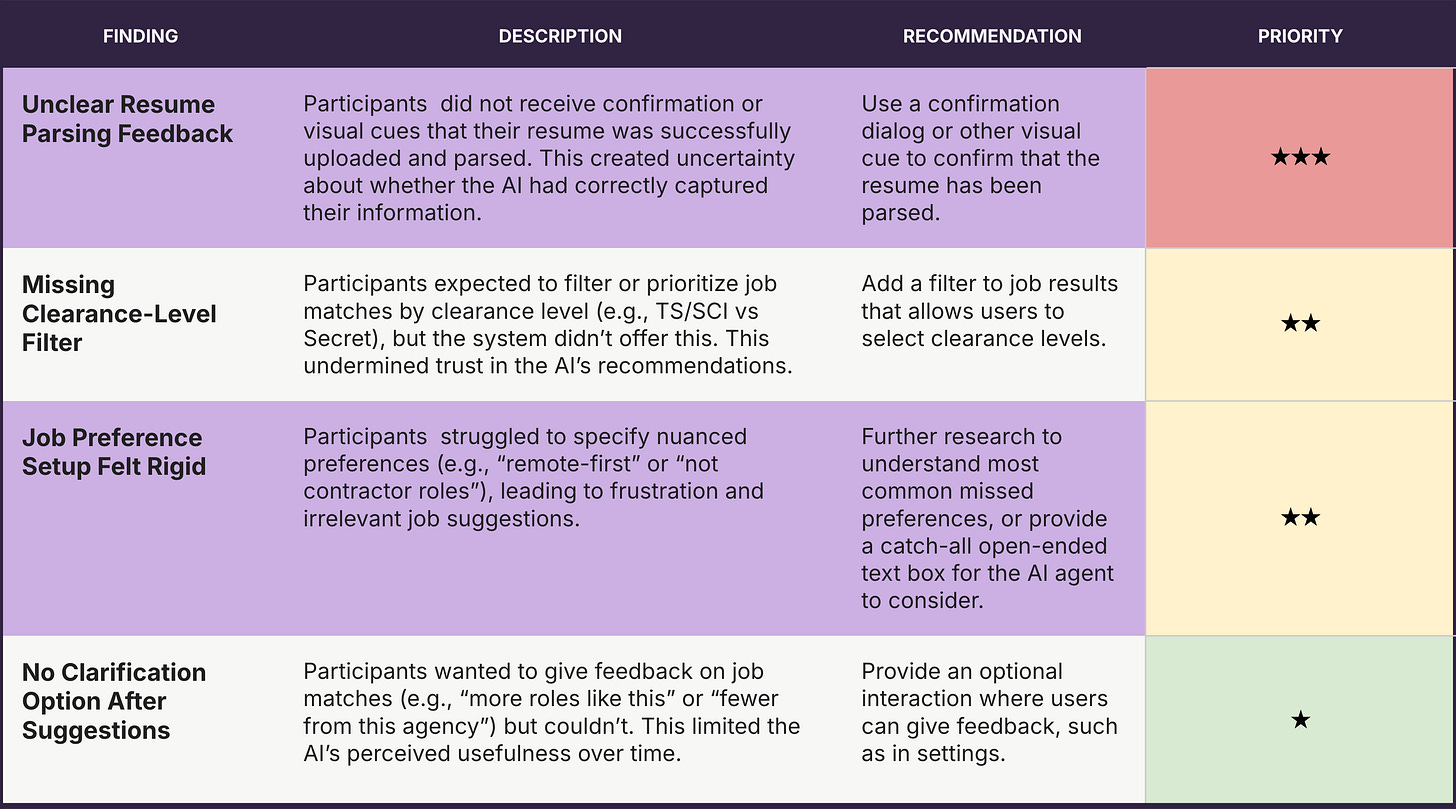

Create scannable recommendation summaries

Whatever prioritization method you use, you should find a crisp and simple visual way of communicating the priority of issues in your report deliverables. One tried-and-true approach is a table with columns for a description of the finding, the implication, the recommendation, and its priority. This final column might use something like a “red, yellow, green” color coding, a star rating system, or even both for multiple encodings.

A sensible place for these tables is near the end of your report deliverable, just ahead of summaries or concluding remarks. Consider also distributing this table separately (e.g., as an embedded image in Slack or an email, or as a standalone PDF) so that stakeholders can pull them up easily for quick access and action.

The bottom line

Recommendations are researchers’ suggestions that stakeholders can accept, modify, or reject to address the negative consequences of a research finding. Aside from a few prescribed circumstances in which researchers should avoid providing them, they may be given at a level of resolution or specificity appropriate for the working dynamics of the team and the researcher’s level of technical expertise regarding their feasibility.

One rhetorically effective way of presenting them is within the FIRE context; that is, after describing the Finding and its Implications, and before describing the Expected outcomes or benefits. Since a single study often generates multiple recommendations, it’s important to prioritize them, considering both the frequency and the severity of issues. Stakeholders are more likely to act upon them when given a summary table with prioritization symbols.

No researcher wants their findings to go un-acted upon. Therefore, given all the advice discussed here, we suggest that you implement these changes to how you present recommendations in research reports. Your stakeholders will more quickly understand why you’re recommending what you’ve recommended and what the impact will be. They’ll also be much more likely to put your suggestions into action.1

In other words, we’re just practicing what we preach… giving you a clear recommendation with an expected outcome. (See what we did there?)