The PAIRED framework for AI in UX Research

A structured approach for assessing the ethical & effective use of AI in UX Research

Since November of last year, ChatGPT has dominated the zeitgeist in innovation, reaching 100 million users in record time.

That excitement also extended to the research and design communities. By our count, since ChatGPT’s release, the tool itself or the topic of AI has featured in roughly 15-20% of articles circulated in popular UX publications. Practitioners are wondering how we could use ChatGPT in our work, how we ought to use AI tools, and what AI means for the future of our profession.

However, the discourse hasn’t yet produced a framework — that is, a formal structured way of thinking through these problems.

Let’s first examine what a good one should have:

Guiding principles

The question is no longer if AI will become a part of common UX research practice, but where and how we should use it. A framework can help provide guiding principles for why, how, and where AI can be most effectively and ethically used.

Adaptability

A good framework can be applied to new systems and situations. Recently, ChatGPT has dominated conversations about AI. But this tool isn’t the final boss — newer AI technology with more robust capabilities will emerge, as will purpose-built UX applications. We need a structured way to think about new tools as they’re released, and how they fit into our practice.

Practical applications

Finally, a proper framework will provide a structured way of holding specific examples against best practices, helping teams to continually evaluate and improve.

The PAIRED framework

After reviewing relevant discourse, we have proposed the PAIRED framework, which defines six core principles for integrating AI tools into UX research: Principled, Accountable, Initiated, Reviewed, Enabled, and Documented.

Principled

UX researchers should define principles for ethical and responsible usage. This clarifies our goals in applying AI to our work, helps us avoid misusing AI, and promotes transparency.

Do:

Individual researchers should reflect deeply on the use of AI in their work and its potential consequences.

UX research teams and leaders should collaboratively explore and define acceptable use cases.

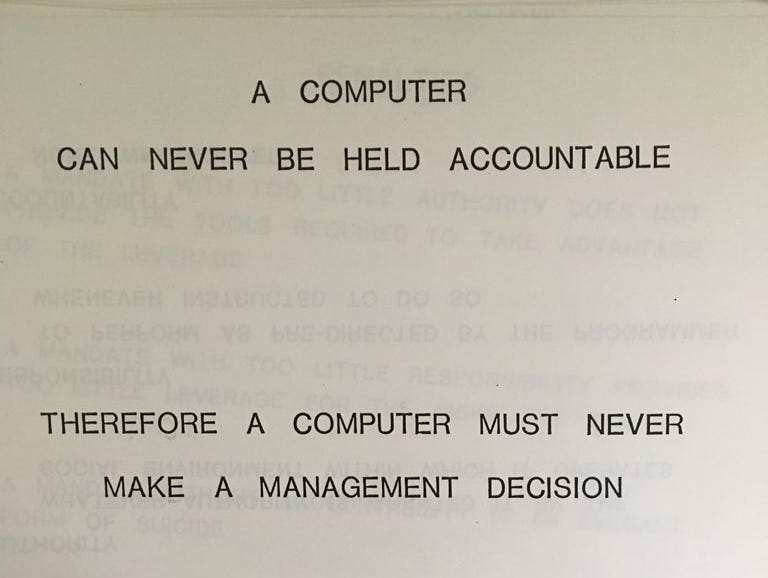

Accountable

AI should support rather than replace UX researchers’ work. By automating repetitive, mundane, and error-prone menial tasks, AI promises more time for researchers to use their critical thinking and creativity. But they remain accountable for the research they produce and the decisions they influence.

Do:

Individual researchers should identify repetitive tasks appropriate for AI, such as coding common sentiments from a large qualitative dataset.

UX research teams and leaders should promote a culture of accountability. Anything presented should reflect the researchers’ thoughts and perspectives.

Don’t:

Although AI may help identify trends or findings, many insights aren’t spoken or come from observed behaviors. Thus, AI-generated insights should only be a starting point — human experts should draw conclusions for product and design decisions.

UX research teams should not fully automate their research projects. Full automation (as opposed to augmentation) would lead to a lack of human accountability for research products and the decisions they impact.

Leaders should not offload decisions related to strategy, direction, and goals to AI systems.

Initiated

AI may be used in workflows, but human researchers should be the ones to begin and lead them. After the tool provides its output, UX researchers review it. Ultimately, they must have the final call for any conclusions and recommendations — or, if need be, corrections. As the Russian proverb puts it: “Trust, but verify.”

Do:

Individual researchers should validate outputs before drawing conclusions or using them in subsequent tasks, e.g.:

AI may clean and prepare data for analysis, but UX researchers should initiate and oversee the process.

AI may generate data visualizations during analysis, but UX researchers should interpret the results and make recommendations.

A UXR might start writing a test script, but use an AI to brainstorm (e.g., a few potential open-ended questions).

A UXR might use an AI system to generate a graph, but then edit it for clarity and accuracy before putting it in a report.

UX research teams and leaders should ensure that any verifiable AI outputs are fact-checked by at least one human expert.

Don’t:

Individual researchers should not credulously accept the output of AI tools.

UX research teams and leaders should avoid fully-automated projects.

Reviewed

UX researchers should thoroughly vet an AI system before using it. Researchers can only ensure a tool is appropriate to use by understanding its capabilities, limitations, and biases.

Do:

Individual researchers should stress test systems using varying prompts and dummy data to understand what influences outputs.

UX research teams should read the documentation for systems under consideration to understand their strengths, weaknesses, and potential biases.

Leaders should assess the team’s work for issues related to AI usage.

Don’t:

When an AI’s data policy is unclear or may otherwise compromise sensitive information, individual researchers should scrub user data before use.

UX research teams and leaders should not endorse unfamiliar AI tools before understanding their appropriate usage.

Enabled

Teams should provide UX researchers with training and resources to properly use AI systems. Thoughtful enablement materials promote a culture of ethical, responsible, and effective AI use.

Do:

Individual researchers should develop a practical understanding of the AI tools they use.

When onboarding new UX researchers, teams should include a module on the responsible use of AI.

Leaders should share success stories where team members have responsibly used AI.

Don’t:

UX research teams should not adopt new AI tools before training.

Documented

UX researchers and their teams should document their use of AI. Aside from specific best practices for using AI tools (see: Enabled), this also means disclosing how AI was used during a project.

Do:

Individual researchers should indicate when AI tools are, or aren't, used in their deliverables. For example, see our disclosure for this article.1

UX research teams and leaders should host AI-related resources in a logical location and periodically revisit them.

The framework in practice

There are two ways to perform a PAIRED analysis when AI is or may be used:

A-priori evaluation of a process under development

Post-hoc analysis of the steps in a recently completed project

For both cases, we’ve prepared a worksheet you can use below.

What’s next?

This article represents an early effort toward guiding principles that offer a structured and replicable way of evaluating the use of AI in UX research settings.

Going forward we would like to:

Have an open discussion about the framework and its concepts

Hear from others who have applied the framework to their processes and projects

Revise the principles, as needed

Provide additional best practices for PAIRED evaluations

The bottom line

Recent breakthrough tools like ChatGPT and Bing Chat have prompted the UX industry to think deeply about how we can and if we should use AI in our practice.

We argue that the train has left the station; it is too late to ponder if we should use AI in our practice, as many have already started to do so. In response, we need to develop a set of principles about how we should apply AI to UXR work. Although many specific use cases are floating around, we don’t currently have an adaptable and repeatable way of assessing the effective use of AI.

What the industry needs is a framework for the effective use of AI in research. To that end, we proposed the PAIRED framework, whose core tenets — Principled, Accountable, Initiated, Reviewed, Enabled, and Documented — may be used to evaluate AI usage during any phase of research, whether a-priori for new processes or post-hoc for completed work.

We hope that the PAIRED framework will be useful to practitioners and elevate the discourse surrounding AI tools. We’ll continue to iterate and refine the framework as the UX research community gains experience from putting it into practice.

AI usage disclosure:

ChatGPT was used to alleviate writer’s block, rework phrasing, and brainstorm. For example, it suggested “the train has left the station” as alternative wording for “it’s too late” in the conclusion.