What is Human Factors?

and why is an HF degree so desirable for UXR jobs?

What is Human Factors?

When looking through UXR job postings, you will probably see a degree in “Human Factors” listed under preferred qualifications. What is Human Factors (HF), and why are HF degrees desirable for UXR roles?

The Human Factors and Ergonomics Society defines Human Factors as:

Human Factors is concerned with the application of what we know about people, their abilities, characteristics, and limitations to the design of equipment they use, environments in which they function, and jobs they perform.

So, HF is the study of the “human factor” in human-technology systems with the end goal of making the system more suitable for the human user. This definition might sound similar to human-computer interaction (HCI) and user experience (UX). HF, HCI, and UX are closely related fields that share a similar goal; designing technology to suit human users. However, they are set apart by their genesis, scope, and application.1

Human Factors (HF)

Broadly focused on human interactions with complex systems

Applications include a wide range of things like aircraft cockpits, cars, and medical devices

An overarching field of study whose contributions have directly influenced both HCI and UX

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI)

Arose during the mass-market computer revolution of the 1980s

“…is a discipline concerned with the design, evaluation and implementation of interactive computing systems for human use and with the study of major phenomena surrounding them.”2

Considered by many to be a sub-field of HF with a narrower, specific focus on computers

More of an academically-oriented field (relative to UX)

User Experience (UX)

Generally agreed that Don Norman coined the term in the early 1990s

Focused on improving users’ interactions with digital interfaces (e.g., consumer or enterprise websites, software, mobile applications, voice agents, point-of-sale systems, screens of any kind, etc.)

More of a practitioner-focused field (e.g., those with careers in “UX” almost exclusively work in industry)

While a UX researcher might have many similarities to someone with a career/background in HCI, the UX field also includes professionals with expertise and roles in design, product management, strategy, copywriting, etc.

What do you learn in a Human Factors psychology program?

Given the attractiveness of a Human Factors degree to those hiring UXRs, you might be curious about what HF students learn.

The curriculum for most HF Masters and Ph.D. programs includes:

Foundational psychology — Courses on human psychology so that students form a foundational understanding of psychological processes. These include topics like cognition, memory, learning, sensation, perception, and physiological psychology.

Human Factors, HCI, and usability methods & assessments — Courses that teach the theory of human-centered thinking and how to apply methods to analyze and improve a system for the end-user. These include topics like Human Factors theory, methods, & application, human-computer interaction, user experience, usability evaluation, and ergonomics & ergonomic assessments.

Research, methods, & statistics — HF programs place a strong emphasis on research. Almost all programs have several courses on research methods, statistics, and ethics. Students in these programs will not only have specific classes on research methods, but most of their other classes have a research component (i.e., a large portion of your grade in a course may be a research project). Further, in many programs, your classwork is secondary to your personal research (e.g., the research you are doing for the completion of your thesis/dissertation and/or grant projects)

Interdisciplinary topics — HF was born from multidisciplinary thinking, so it is no surprise that HF students have a wide range of elective courses in visual & graphical design, linguistics, technical writing, industrial systems engineering, mechanical engineering, neuroscience, and more.3

Human Factors research examples

As mentioned above, performing research is a focal point in most HF programs. I had the pleasure of attending HFES 2022 last month, where many graduate students present research they have undertaken as part of their studies. I’ll highlight a few of my favorites as examples of what HF grads study:

The Bottom Line: Why a background in Human Factors is sought-after for UX roles

Individuals should carefully consider whether grad school is right for their career goals, and how companies they apply to will count time in grad school as work experience, but HF psychology programs are a great choice for aspiring UXRs. The close relationship between the fields of HF and UX, the exposure to interdisciplinary perspectives, intense training in human-technology system evaluation, and experience applying research methods give HF degree-holders skills and knowledge that directly transfer to a role as a UX researcher.

Bonus: Why do we call all these things “slider scales?”

What do we mean when we say “slider scale?” Why do we use a single term for survey items that take on several forms? Recently I found myself asking these questions. It might sound silly, but have you ever stopped and looked at all the differences in survey items lumped under the umbrella term “slider scale?”

Take the gifs above as examples. Ignoring what they’re meant to capture for a moment, look at the different setups of each one. Their only commonality is the UI pattern, a draggable indicator along a fixed-line. How the line is anchored, whether the scale is subdivided, whether or not a value is displayed for the response, and whether the respondent can select any value along the continuum or if there are fixed values, all differ.

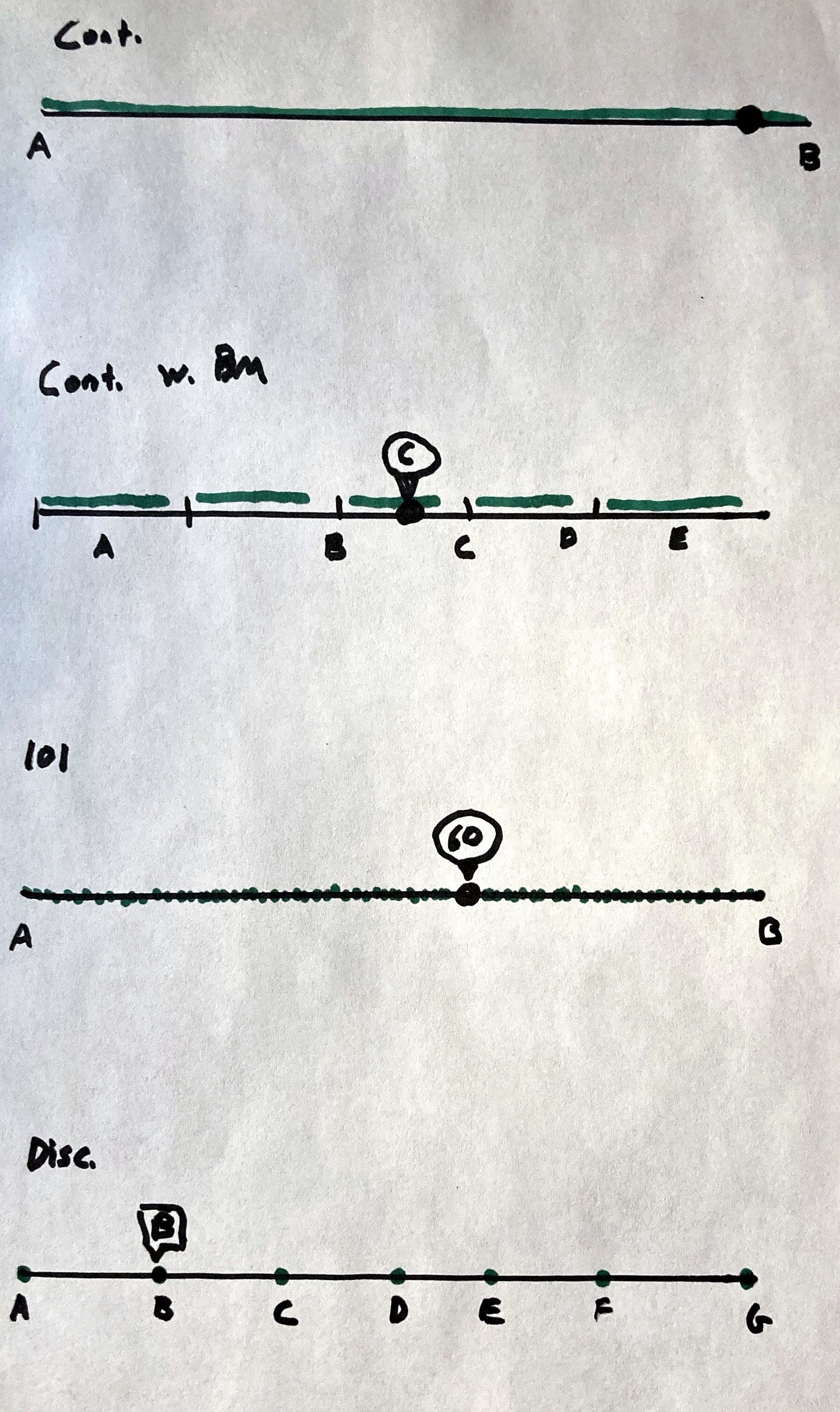

It seems like four types of slider scales are commonly used. Here’s a literal back-of-napkin sketch I used to describe it to a friend:

Continuous — The scale sits between two endpoints, “A” & “B.” Respondents can freely move the indicator to any point along the line, using the space as a metaphor for how much like “A” or “B” their feelings are.

Continuous with benchmarks — Similar to the continuous version, respondents can freely move the indicator to any point along the line and are instructed to use the space as a metaphor for their subjective perception. The difference, in this case, is that the scale is divided into ordinal ranges with cutoff values (e.g., great>90, good>75, fair>60, etc.).

101-point scales — A scale ranging from 0 to 100, where a slider is used rather than displaying 101 separate Likert-style buttons. It should be noted that this is functionally very similar to how the continuous example works on the backend (the spatial response is typically converted to a 101-point response). The main difference, in this case, is that the respondents are shown the numerical value while the continuous response is a purely spatial analog task.

Discrete — The scale has discrete points (A, B, C, etc. in the above example) represented on a line. The respondent can only move the sliding indicator to one of these values. To me, this is the most strange use of a slider scale. Aside from the modality a respondent uses to give their response, it is functionally no different than a Likert scale.

Depending on who you talk to (and what survey tool they use) they might mean any one of these four when they say “slider scale.” This might or might not be problematic for researchers. We know that variations in how response options are framed can impact participants' response patterns, so these similar but meaningfully different types of slider scale formats could have an impact on our results. I know that there has been plenty of research comparing sliders with Likert-type scales, but none (that I have seen) directly compares these different forms of slider scales.4

Whether these different slider formats affect response patterns is an empirically testable question. I also doubt I’m the first to raise it, so I have some desk research to do. I’ll likely follow up in a future issue if I find compelling evidence, especially if it is applied to subjective usability ratings.

Please note — the distinctions between these fields are ill-defined. These bullet points are here to give you a relative framework for what sets them apart and shouldn’t be seen as definitive

Taken from Hewett et al., 1992

Here are a few links to different programs’ curricula in case you’re interested: North Carolina State University, Clemson, George Mason, Embry-Riddle, University of Minnesota