Frequently confused words and phrases in UX research

Clarifying the terminology behind many misunderstandings

“By the end of that meeting, I was so mad that I literally set my laptop on fire.”

What about that statement stands out to you? If you bristled at “literally” being used to mean its opposite (i.e., figuratively), you might be a prescriptivist.

Language is alive. It evolves through usage. For any given term, there’s the prescriptive sense found in formal definitions, and a descriptive sense that reflects how people use it. The problem is that, in a way, both are correct! For example, “literally” has been used in the figurative sense widely enough that it now has a corresponding secondary definition.

It’s no surprise then that this also applies to the terms we use in UX. Whatever our understanding of words, our stakeholders — or at times, even our colleagues — might have a very different definition. So from time to time, we leave meetings confident we’ve reached consensus, only to later discover we walked away with opposite conclusions. That’s enough to make you want to set your laptop on fire (figuratively, of course).

Miscommunication happens in many ways, but most can be avoided by defining our terms. In this article, we’ll look at some of the most commonly confused words and phrases used in UX research, so you can recognize them, clarify them, and avoid misunderstandings.

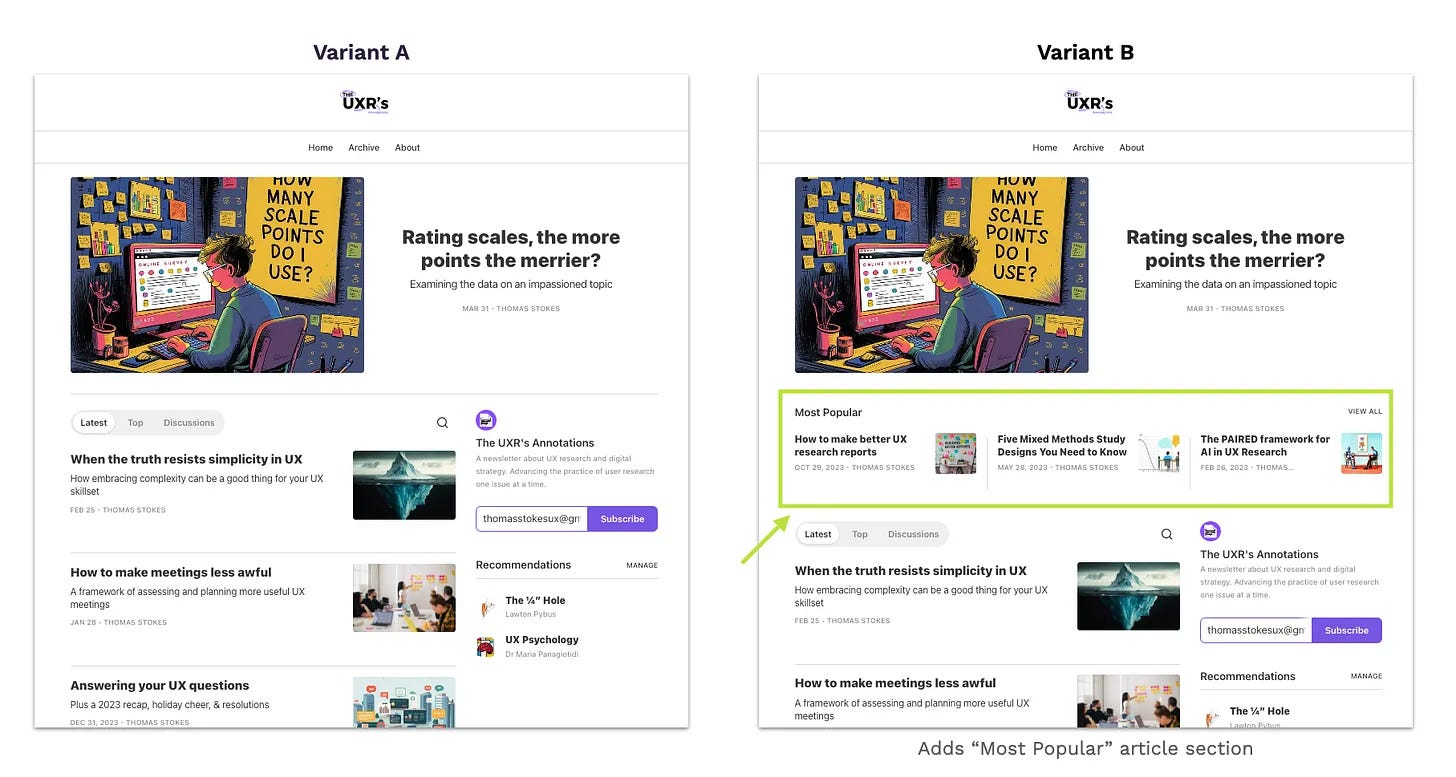

A/B Testing

How it’s often used: Any user research study that compares two variants (or options, e.g. A vs. B). This might include comparative usability studies, preference tests with concepts or prototypes, or similar methods. For example…

Researcher: “We recruited 10 participants and did an A/B test of the two prototypes, and found that users preferred B in 4 out of 5 dimensions.”

A more precise understanding: A quantitative test that exposes thousands (or even millions) of users, usually without their knowledge, to different design variants in a live product. The winner is determined based on statistical analysis of concrete behaviors, such as conversion or open rates.

Product and engineering teams will often be familiar with the latter, as they tend to collaborate with analytics and data science teams to develop, run, and analyze A/B tests of this kind. It’s a great way to quickly settle debates on smaller, incremental changes to a live product when a typical research study might not be worth the time and hassle.

On the other hand, smaller sample user research studies are great for finding the strengths and weaknesses of designs at an early stage of development. In fact, a comparative usability study can make a later A/B test more effective by identifying what are the most valuable variants to test, and why.

Survey

How it’s often used: Any form of research or user feedback, whether formal or informal. For example…

Stakeholder: “We came to your team because we know we need a survey.”

A more precise understanding: A set of standardized questions administered to a sample of online research participants, usually using tools like Google Forms, Qualtrics, or Tally. It’s intended to collect a large volume of data in a relatively short time and at a relatively low cost. It can be contrasted with other remote, unmoderated methods, such as unmoderated usability testing. Further, surveys can be the vehicle for sophisticated methodologies such as Kano, conjoint, and Key Drivers Analysis.

When “survey” is used as a catch-all term for research, it may signal a limited understanding of research methodologies. Think about it: even if you don’t know much about research methods, you’ve probably seen, taken, or even designed a survey. But you’ve also likely encountered poorly-designed surveys with leading questions and incomplete response options. Though surveys are both common and powerful tools, designing an effective one can be surprisingly nuanced.

In short, don’t take a stakeholder’s request for a survey at face value. A survey may be the right tool, but there may be a better alternative.

Interview

How it’s often used: Any form of scheduled research session with participants or representative users, such as usability study. For example…

Stakeholder: “What did you learn from those interviews last week?”

Researcher: “Wait, was someone on the team running interviews?”

A more precise understanding: A one-on-one session with a participant, primarily consisting of a structured or semi-structured conversation designed to answer specific research questions. See also: in-depth interviews (IDIs), or user interviews

Like “survey," the term “interview” is often used more broadly by non-researchers than by researchers. Because researchers have a deeper understanding of methodologies, we tend to use more precise terminology. If the session primarily involves interacting with stimuli (i.e., a prototype, website, or app), we would consider it a usability study. However, many non-researchers might be hard-pressed to define the word stimuli, so the catch-all term “interview” seems appropriate.

This can lead to confusion when stakeholders request or describe “interviews.” If in doubt, ask follow-up questions or clarify with examples.

Quantitative

How it’s often used: As a synonym for reliable or trustworthy, implying that data from these studies is inherently more robust because its methodology (e.g., A/B tests, surveys, remote unmoderated studies) allows for large sample sizes. For example…

Stakeholder: “It’s interesting that only 1 of the 5 participants finished the task… but we have quantitative data showing that it works fine.”

A more precise understanding: Numerical data about users’ attitudes and behaviors. Common methodologies for collecting such data include A/B tests, surveys, and remote unmoderated studies. Quantitative research is most useful for tracking trends over time, comparing data points, or measuring the scale and impact of an issue or finding.

Although “quantitative” is often associated with reliability, the term itself says nothing about the trustworthiness of the data. A remote unmoderated usability study with over 1,000 participants could still be unreliable due to issues such as incomplete or inauthentic responses, insufficient statistical power (e.g., dividing participants across 50 variants), or poor study design.

Likewise, we know that if only one out of five participants completes a task, it doesn’t mean exactly 20% of real-world users will succeed. But even with this small sample, we can calculate 90% confidence intervals and estimate that fewer than 58% would complete the task. If we replicated the study with a larger sample — say, 500 participants, where 100 successfully complete the task — the upper bound of our confidence interval would drop to 23%, much closer to the observed 20%.

So while it’s true that a well-executed quantitative study provides more reliable estimates, that reliability depends on more than just the sample size. When precision is necessary and resources allow, quantitative research can be invaluable. But it isn’t inherently superior to other research methods and shouldn’t be pursued for its own sake.

Intuitive

How it’s often used: Describes a design that is easy to use, generally pleasing, or subjectively “good.” For example…

Stakeholder: “The main thing we want to know is: is the new experience intuitive for users?”

A more precise understanding: “Familiar, or … uses readily transferred skills.” This definition comes from Jef Raskin, an early Apple employee and HCI expert, who explored this concept at length in a well-known paper (and highly recommended read). Even in 1994, Raskin noted that the most common request in design was for an “intuitive” experience.

Raskin pointed out that, when understood as “familiar,” an intuitive design cannot be significantly different from what people already know. This creates a paradox: since the biggest improvements are often drastically different, a substantial improvement may be rejected on the grounds that it doesn’t feel intuitive. Thus, one reason to get clear about what we mean by “intuitive” is to recognize its implications for our product.

Another reason to define “intuitive” more concretely—by operationalizing it—is that it makes measurement possible. Instead of using it as a vague, aspirational synonym for “good,” we can specifically assess how well a design reflects familiar systems and tools that users already know.

Insight

How it’s often used: As a synonym for data or findings, particularly when they are actionable. According to a literature review by researchers Battle and Ottley, it’s also common for scholars to use the term to refer to either “summary observations about data” or “descriptions of data that support a specific conclusion.”

Stakeholder: “We were hoping you can give us some insights about how people use the customization tool.”

A more precise understanding: Merriam-Webster defines insight in two ways: “1. penetration, or the act of seeing into a situation; 2. the act or result of apprehending the inner nature of things or of seeing intuitively.” In other words, it’s seeing clearly both the trees (the details, data, and findings) and the forest (the big picture, meaning, or implications).

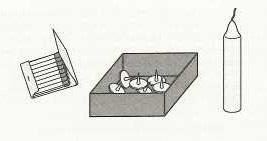

A good illustration of this definition comes from the early study of the term in the context of problem-solving by Gestalt psychologists. While many problems can be solved with incremental, step-by-step progress, others — called insight problems —may appear unsolvable for a time. However, a sudden shift in perspective can reveal the solution.

One famous example is the candle problem, in which the solver is given only a candle, a matchbook, and a box of thumbtacks. The task is to mount the lit candle on the wall in such a way that melted wax won’t drip onto the floor. If you’re unfamiliar, take a minute to try to solve it yourself before reading the solution.

In an era when product teams are under increasing pressure to get insights faster, this definition helps to underscore our key value proposition as professional researchers. It’s true that an LLM can summarize (or, to be more exact, mechanically shorten) an interview transcript. But these tools struggle to truly connect the dots. Unlike human researchers, they lack the domain knowledge and contextual understanding required to interpret not just what was said, but why it matters.

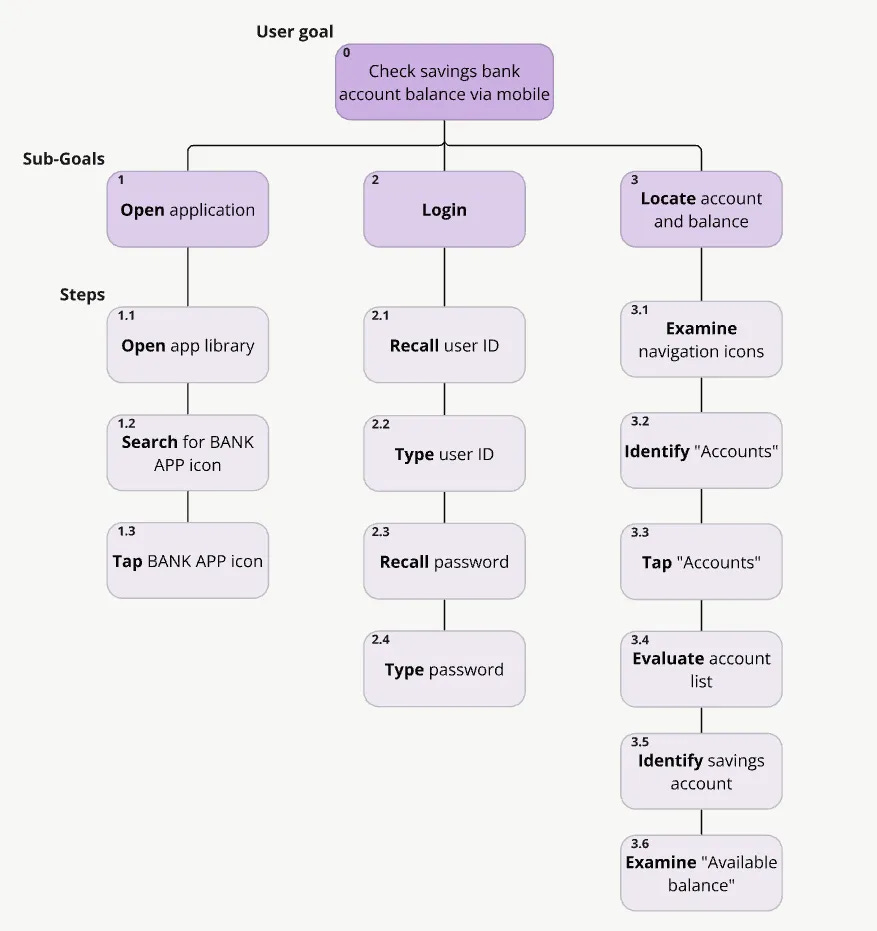

Task Analysis

How it’s often used: Any method using the task as a fundamental unit of analysis, such as task-based usability studies, or diagramming user flows. For example…

UX Pro: “While we’ve been finalizing the journey maps, the design team has been doing a task analysis of the payment flow.”

A more precise understanding: A set of formal approaches that defines a task and decomposes it into more fundamental elements, such as sub-steps or sub-goals, to identify strengths and opportunities. It comes in a variety of flavors, such as a GOMS-based task analysis or a hierarchical task analysis.

In other words, while it may sound like a generic approach, task analysis has a specific meaning in the context of human factors, which is one of the forebears and sister disciplines of user experience. Before you dismiss it is a purely academic method, note that it is one of the most commonly used human factors techniques in applied settings. And although it’s underutilized in UX, it may be put to fruitful use in the work we do.

ROI (Return on Investment)

How it’s often used: The financial benefit of a product enhancement made as the result of UX involvement, such as cost savings. For example…

Researcher: “Our research suggests that the auto-enroll feature, if implemented, would produce an ROI of nearly $25,000 per month in additional revenue.”

A more precise understanding: The financial benefit of product enhancements expressed as a function of the investment required to produce them.

To illustrate, imagine you’re running a stand selling lemonade at 25¢ per glass. Your revenue, or return, would be determined by the quantity of glasses sold. However, the ROI would also account for the cost to produce each glass. If it costs more than 25¢ to make a glass, you would have a negative ROI!

Often return is often discussed without considering the required investment. This may be a simple oversight, as many UX practitioners are not business owners or accountants familiar with these calculations. It might also be because investment figures can be difficult to obtain, especially for individual contributors without purchasing authority or visibility into budgets.

Nonetheless, there are good reasons to overcome these obstacles. Greater business acumen allows UX professionals to understand how the different components of an organization contribute to its success, making them more valuable partners. And even if investment figures are not precise, using estimates can help to create a more compelling picture of the value added by UX efforts.

If you’d like to learn more, Depth previously published an article that offers further explanation and examples for making calculating ROI based on your scenario and data.

Let’s be good communicators

Jargon is inevitable in any specialized field, but as UX professionals, we must strive for clarity. Clear language is the product of clear thinking. If we know what we’re saying, it’s a good sign that we also know what we’re doing. On the other hand, vague or muddled language can hurt our credibility.

We also can’t assume that others understand the terms in the same way we do. Instead, we should take the time to clarify meanings and check for mutual understanding. Simple follow-ups like, “Could you tell me more about what you envision in this survey?” or “What kind of outcome are you hoping for with an intuitive design?” can prevent confusion down the line.

This is not an exhaustive list of problematic terms in UX research. Some would argue that the very name of our field — user experience — is the thorniest. And since we as a discipline love to refresh and rebrand our terminology, a phenomenon Jakob Nielsen refers to as “vocabulary inflation,” misunderstandings can grow worse over time if we’re not careful.

That’s why it’s essential to recognize commonly misinterpreted terms and use them as opportunities to establish a shared understanding. By doing so, we strengthen our communication and, ultimately, our impact as UX professionals.